CHOLERA

OVERVIEW & RESERVOIRS

WHAT IS CHOLERA?

Cholera is an acute diarrhoea infection caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, a curved, comma-shaped, motile, Gram-negative bacterium that lives in aquatic environments.

This bacterium spreads through contaminated food or water. It leads to severe watery diarrhoea and rapid loss of fluids and electrolytes, which can cause dehydration and even death if left untreated. Cholera is a major public health threat, especially in areas with poor sanitation, limited access to clean water, and overcrowded living conditions due to poverty, war, or natural disasters.

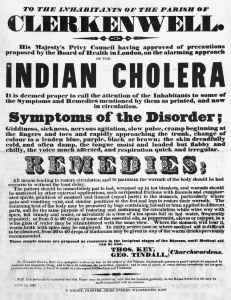

BRIEF HISTORY OF CHOLERA

The disease, Cholera, has been around for centuries. The Greeks named the disease “cholera” which originates from the Greek term “cholades”. The word is derived from chole (bile) and rein (to flow), referring to the disease’s association with fluid loss. The ancient physician Alexander Trallianus (also known as Alexander the Great) suggested that “cholades” referred to the intestines, as cholera often caused severe watery diarrhoea rather than bile-related symptoms.

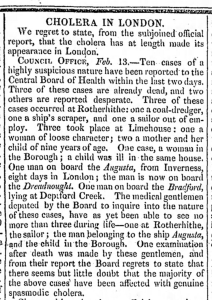

Virbrio cholerae was at first only present in Asia until an outbreak spread to nearby regions such as India and Indonesia in the 18th century. In 1854 John Snow investigated an outbreak in London and discovered the Vibrio cholerae bacteria. Robert Koch also discovered Vibrio cholerae in India during 1883, this aided in the Germ Theory for diseases which was a debate of the time.

Centuries after the discovery of the bacterium, Cholera is still a dangerous disease that causes severe pandemics. This is due to socioeconomic impacts such as poor sanitation, rather than inadequate research. It is therefore critical that the causes, treatments and prevention of Cholera are communicated.

CAUSES OF CHOLERA

Vibrio cholerae, the pathogen of Cholera, lives in warm, brackish water. When a person consumes water or food contaminated with this bacteria, it attaches to the walls of the small intestine and releases a toxin. This toxin triggers the body to release excessive amounts of water, leading to severe diarrhoea, rapid dehydration, and loss of essential salts (electrolytes). For more information on Vibrio cholerae visit our morphology page.

Contaminated water supplies are the main source of cholera infection. The bacterium can be found in:

- Untreated surface or well water

- Raw or undercooked seafood, especially shellfish from certain regions such as the United States and the Gulf of Mexico

- Raw fruits and vegetables that are grown with contaminated water or fertilizer.

- Cooked grains like rice and millet can support bacterial growth if left at room temperature for several hours.

- Poor sanitation and crowded living conditions increase the risk of widespread infection.

Not everyone exposed to V. cholerae falls ill, but infected individuals can still pass the bacteria through their stool, contaminating water and food supplies.

CHOLERA TODAY

Modern water and sewage treatment have nearly eliminated cholera in developed nations, but outbreaks still occur in regions like Africa, Southeast Asia, and Haiti. Natural disasters and heavy rainfall can increase the risk by contaminating water supplies.

In addition to contaminated water, cholera can also spread through raw or undercooked shellfish. Prevention focuses on improving sanitation, providing access to safe drinking water, and maintaining good hygiene. Early detection through strong surveillance and prompt treatment can save lives and reduce the impact of outbreaks.

Read more about the community impact of Cholera and preventions strategies taken in the modern age.

RESERVOIRS: WHERE V. CHOLERAE THRIVES

Several studies have investigated possible areas where Vibrio cholerae multiplies, lives and survives inter-epidemic periods. These areas and conditions are called reservoirs. These studies have looked at animals, humans, and the natural environment as reservoirs. The studies have proved that Vibrio cholerae reservoirs are only the natural environment, as it thrives independently in aquatic environments.

When Vibrio cholerae is exposed to unfavourable environments such as low temperatures or insufficient nutrients, the bacterium goes in a dormant state. Interestingly, it receives support from Cyanobacteria, a type of algae found in freshwater and seawater. Vibrio cholerae remains dormant until a seasonal algae bloom occurs, this creates a nutrient-rich environment and therefore activates Vibrio cholerae again. This results in the release of Vibrio cholerae and consequently leads to a seasonal outbreak of Cholera.

To sum it up, the natural reservoir of Cholera includes rivers, lakes, plankton as well as polluted water. It is important to note that humans also serve as reservoirs when they ingest contaminated food or water. Since the bacteria colonise the intestine, they are excreted in faeces, contaminating water sources and further spreading the disease

CHOLERA PANDEMICS

Cholera has caused multiple pandemics throughout history:

- First Pandemic (1817–1823) – Began in Jessore and Calcutta, spreading across India.

- Second Pandemic (1823–1837) – Originated in India and spread to Russia, Poland, Germany, Sweden, Australia, and England by 1832.

- Third Pandemic (1846–1863) – A severe outbreak that spread from Bombay to Egypt, then to Europe and the Americas, mainly via maritime trade.

- Fourth Pandemic (1864–1875) – Continued to spread across Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

- Fifth Pandemic (1881–1896) – Affected Egypt, Asia Minor, and Russia.

Cholera spreads primarily through contaminated water, making it easier for the disease to travel across regions.

THE FIRST CHOLERA EPIDEMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY

During an early cholera outbreak in Paris, observations were made and records of 1105 reported cases were taken. Chevalier then later noted some houses which reported up to 11 deaths which their raised concerns. Statistics had to be taken into consideration and investigation needed to be made to help dig more information related to this disease to help stop the spread since people died.

REFERENCES

Pruthi, S. et al. (2022) Cholera, Mayo Clinic. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cholera/symptoms-causes/syc-20355287 (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

Cholera (2024a) World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

What is cholera? (2025) Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16636-cholera#symptoms-and-causes (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

Montero, D.A. et al. (2023) vibrio cholerae, classification, pathogenesis, immune response, and trends in Vaccine development, Frontiers in medicine. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10196187/ (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

https://biologyinsights.com/Cholera-transmission-and-environmental-reserviors/

https://cahc.jainuniversity.ac.in/assets/ijhs/Vol47_3_2_SSen.pdf

https://link.Springer.com/article/10.1007/500248-003-2007-6#sec7

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/pmc3842031/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44446659?seq=13